Are exams necessary in a survey course on the history of American journalism?

Are exams necessary in a survey course on the history of American journalism?

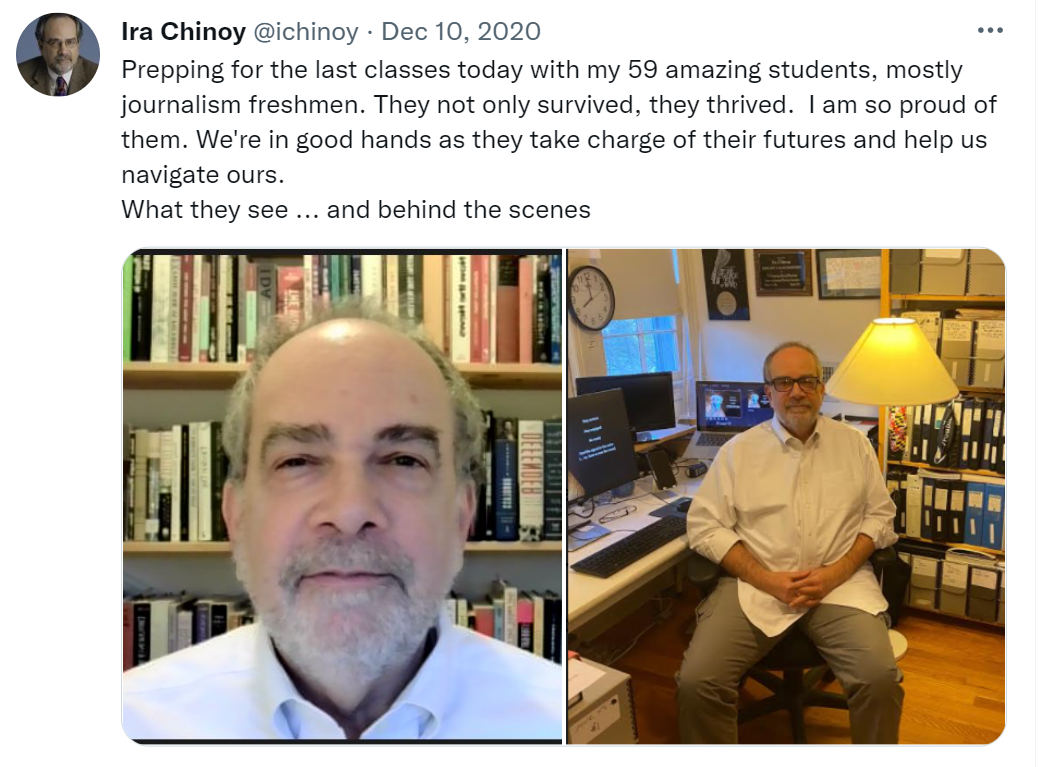

I asked myself this as I prepared for teaching in the first full semester of the pandemic. I would have 59 students in two classes. They would be freshmen taking their first course in the journalism major. Their transition from high school would be on Zoom.I was so apprehensive that before the fall semester, I reached out to each student individually – via email and then Zoom – to make a connection. I was delighted to see how eager they were.

I dreaded giving timed exams online, especially if students would be ill or in quarantine. I recalled the cramming students do in the days before midterms and finals. What’s jammed into their brains doesn’t have much of a shelf life. I wondered if marathons of cramming could be replaced with opportunities each week for students to capture what strikes them as important and do some critical thinking. What if students could keep journals and use the entries to craft midterm and final essays – with prompts addressing themes of the course?

I decided on Adobe Spark for what I called a “personal learning journal.” Spark makes a simple web page with text and multimedia elements. Students could share the URL with me rather than posting to the open web. I thought that if I could master Spark in minutes, so could they.

Each week, students got a new prompt. In the second week, the prompt included this: “Make an entry … on ways that tensions between freedom and repression of the press played out in the time period we are covering this week - from Publick Occurrences to the Partisan Press era. Include a connection you might have made to whether you see these sorts of themes playing out today.”

Although this was not a newswriting class, they did write a research profile of a historical journalist plus several “reflections” on current news stories. These allowed me to help with writing. We talked about “mastery,” and we looked at primary sources to see the evolution of newswriting over time. One journal prompt said, in part, “I would like you to reflect on whether and how any of the material we covered has inspired you or surprised you in any way as you think about your own writing.” The entries were not graded for writing quality but figured into class participation scores. I provided individual feedback on the journals every three weeks. And I let students know well ahead what the midterm and final essay prompts would be.

The students took to the journals. And I could tell in real time what was resonating with them. I treasure this from one entry after we read Ida Wells: “This queen wrote what she wanted and changed the world...” The same student included this in her entry on the Black press: “Very important moment for me. Inspires me to keep going even though times are tough.”

In the spring, when my students came from many majors, the journals worked just as well. A theater major wrote: “… having more chances to just explore what I was learning from the course really helped – way more than traditional exams ever could… I also think it helped my writing relax.” A student who plans to be a music teacher wrote: “I have never been so emotionally attached to a school assignment in my life.”

In the end, I am glad the pandemic forced me to rethink how we teach, how students learn and how we assess what they have learned.

Ira Chinoy is the winner of the 2021 National Award for Excellence in Teaching. A Pulitzer Prize-winning veteran journalist with 24 years of experience at four newspapers, Chinoy has been on the faculty at the University of Maryland's Philip Merrill College of Journalism since 2001.