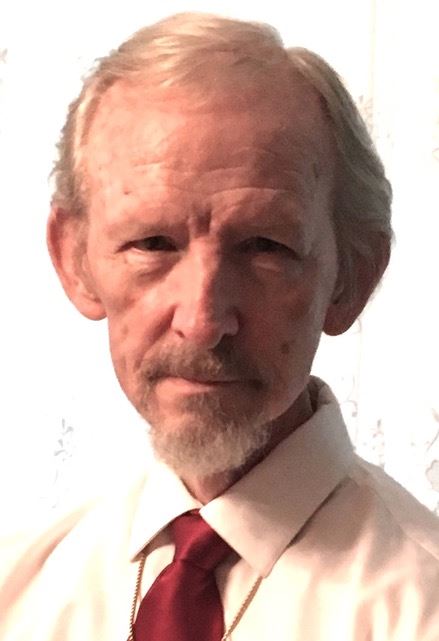

by David Sloan, University of Alabama (emeritus)

One of my brothers died in April, and family members, including his wife of fifty years, were uncertain about such basic details as where he served in the Army and even where he was born.

One of my brothers died in April, and family members, including his wife of fifty years, were uncertain about such basic details as where he served in the Army and even where he was born.

When people die, think of all the knowledge that vanishes with them.

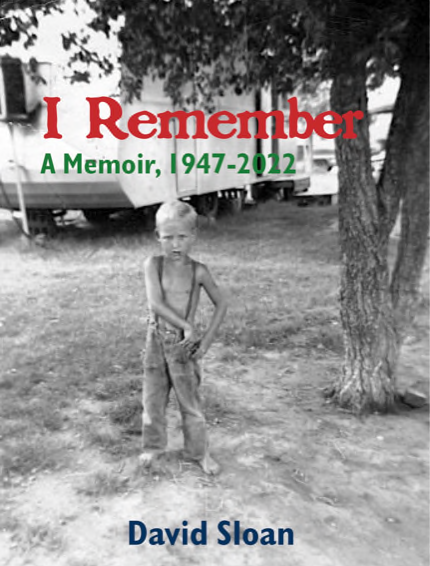

So it wasn’t a grandiose vision that led me to write my memoirs. It was a simple plan. I wrote my memoirs mainly for my two children and five grandchildren. If any of them should want to know something about me after I’m gone, maybe they can find it in my memoirs. If they’re not interested, perhaps years from now a descendent unknown will be.

Because the memoirs are primarily for my family, they tell of such things as how I spent my childhood, what I did in high school, how I decided as a college freshman that I wanted to be a professor, how I met my future wife by a singular coincidence, and what I did on my four newspaper jobs.

But since I spent much of my life in academia and history, a large part of my memoirs covers those areas.

Even though the largest portion of my time as a professor involved the study of history, it was not my original plan. I had intended to specialize in law in my doctoral program at the University of Texas. My decision to switch to history surprised even me.

I got hardly any guidance as I studied history. Yet my dissertation opened my eyes to some of the biggest problems that plagued the study of JMC history.

When I was trying to choose a dissertation topic, my committee gave me only the most meager idea about what to do. My advisor came to the rescue. He told me, “Choose something no one’s ever studied.”

That sounds simple enough. But consider: How can one be aware of something in history that no one has ever written about? It’s not easy. I went ahead and tried to come up with something. Later, it dawned on me that the reason no one has written about some topics is that no one’s interested in them. They’re unimportant or, worse, boring.

I suggested the party press from 1789 to 1816 as my topic. Hardly any historian had written about it in the 20th century. In fact, historians had disparaged it since long before I was born. They gave it the sobriquet “The Dark Ages of American Journalism.”

As I read through hundreds and hundreds of primary sources, something strange kept popping up. Historians said the newspapers were terrible. But people of the time thought they were important. They even praised the papers! Can you imagine that? How could they be so misinformed? Didn’t they realize that the papers weren’t doing the proper job of newspapers?

Then it struck me. Historians were the ones who got it wrong. They were judging the newspapers by journalistic standards that only appeared later. They were expecting editors of the party period to perform by criteria of the historians’ time.

The problem, present-mindedness, is well-known to historians, but journalism historians in 1980 were oblivious to the error.

Once I realized where the problem lay, I could see all of journalism history in a new light.

My dissertation planted the seed for much of the research and writing that I did in my academic career.

The greater portion of my efforts was aimed at trying to improve practices in our field and to elevate history’s importance in the broader field of mass communication education.

One of the biggest efforts was the AJHA. Gary Whitby and I started it in 1982, and Gary founded its journal, American Journalism. Ten years later, I started the AJHA Southeast Symposium, and even after retiring from teaching I created the online journal Historiography in Mass Communication. My memoirs detail each of those efforts.

They were of great importance for me, but I spent more time on writing and editing books. Several focused in some way or other on historiography.

The first one was American Journalism History: An Annotated Bibliography. I won’t waste words explaining why I did it, but will only say that it was mainly for my own benefit. I figured that, to be a historian, one needs to be familiar with the literature in the field. I began work on it the summer after completing my dissertation, and over the next eight years read more than 2,600 books and articles. It was the best education I ever got.

My original plan in compiling the bibliography was to identify the various schools of JMC historians and explain their interpretations of the major periods and topics in the field. That effort eventually led to the book Perspectives on Mass Communication History.

At the same time I was working on Perspectives, Jim Startt and I began Historical Methods in Mass Communication. Jim knows more about historical methodology than any other JMC historian ever has, and his expertise shows in that book. I estimate that around 2,000 students, as well as some professors, have learned how to do historical research from it.

Not all books were so esoteric. The first edition of The Media in America was published in 1990. With it, my goal was to provide an accurate and authoritative textbook that gave students a good historical grounding. It is now in its eleventh edition.

I worked as a professor for thirty-eight years. I had a privileged life.

When my two grandsons were small children, they were riding with me through downtown Tuscaloosa on a hot August day. A construction crew was hard at work on a new hotel. Matthew and Garrett knew I was a professor and had an office job.

Matthew, five years old, watched the workers. He declared, “Some people have to work like dogs.”

He paused and then added, “You know, Grandad, you’ve got the greatest job in the world. All you have to do is sit down all day — and do nothing.”