By Teri Finneman

I still vividly remember grabbing the newspaper off the kitchen table and hurriedly slamming through the pages.

Somewhere, in the middle of the paper, there it was: my very first byline. I was 17 years old and now a real journalist for the newspaper of my hometown of 2,500 people.

I often say I owe everything I have today to my work with weekly newspapers between the ages of 17 and 22. After that, I dared cross that red line over to the world of dailies, one I swore I would never cross.

In 2014, I returned to the world of weeklies when I partnered with the North Dakota Newspaper Association to capture oral histories of older/retired North Dakota journalists. I’ve been doing that work ever since. I frequently guest speak at state newspaper conventions throughout the Heartland, where I mingle with community journalists and return home to the world of weeklies.

Therefore, when I finally got the opportunity to teach journalism history, it was important to me to highlight community journalism history. After all, as Reader (2018) notes, there is little prior research focused on U.S. weekly newspapers despite the fact that “community newspapers, the vast majority of them weeklies, accounted for 85 percent of all newspapers in the United States and for three-fifths of overall print circulation” in 2015.[1]

I wanted to go beyond journalism history in New York and Washington, D.C. I wanted journalism students to be told that a career in community journalism was just as important as one in the big cities.

Early in the fall semester, I invited the Kansas and South Dakota newspaper associations to talk to my history students about why community journalism matters. They impressed upon Generation Z that community journalism can align with their values of entrepreneurship, putting their multimedia skills to use while advocating for a community.

From there, I divided my class of 34 students into seven groups. I had already worked with the Kansas Press Association to identity seven notable journalists in the state to work with us so students could capture their oral histories. By the end of the semester, the class presented nearly 570 pages of new Kansas journalism history to the state historical society.

I began the assignment process by giving the students an overview of how oral history differs from journalism. I learned from my prior experience doing a similar project in South Dakota that it was best for me to be the one to go over the legal paperwork with the subjects. I also provided the students a base list of 100 questions that I ask of all of my oral history subjects. From there, it was on their group to complete the rest.

I am a big proponent of group contracts for group projects where every single task is written down and a student’s name is placed in front of it. Then, it is crystal clear who is in charge of (and accountable for) what. Students divided up research on the journalist, additional question development, the interviewing process, audio editing, transcript proofing and corrections, social media posts, and biography write-ups.

The pandemic created some issues in that I usually block off a whole day for collecting oral histories in person. Instead, we needed to use Zencastr and train our subjects how to log into that system so that students could remotely capture their audio through their laptops from home.

The students ended up having long phone calls with their journalists instead of video taping with them in person. They took turns interviewing their assigned journalists and hearing their life stories.

It was disappointing the students couldn’t meet these journalists in person. But even with the altered and distanced assignment, the impact on Generation Z was clear:

Doing the oral history project was one of the most fascinating things I have done. Talking to someone who made a profound impact in journalism history was like jumping into a book and seeing everything firsthand. Buzz Merritt is a very multi-dimensional man with a lot of great stories to tell. It was very different from just reading a history book because I learned about how his family dynamic, his favorite parts of the job and things he wants us to know. Participating in this project not only taught me more about journalism history, but also introduced me to an entirely different generation and how it made journalism what it is today.

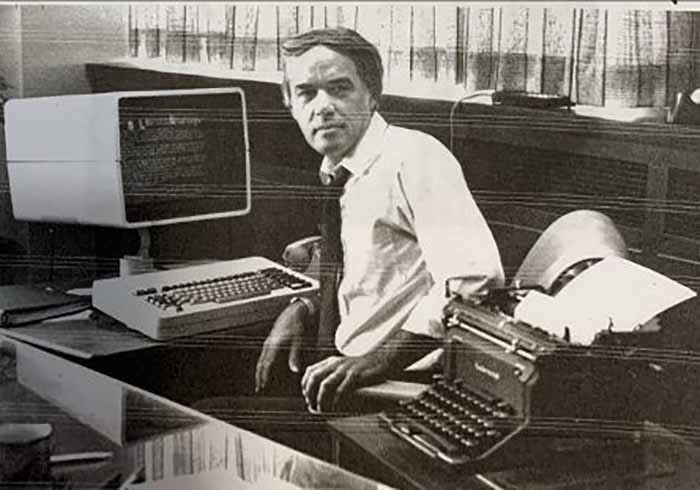

Kansas journalist Buzz Merritt is pictured at his desk with two generations of newspaper technologies. Credit: Buzz Merritt.

Throughout this oral history project, I have learned just how important it is to document journalism history. This was one of the most rewarding projects I have ever had the opportunity to be a part of. When interviewing Craig McNeal, I was so impressed and fascinated with everything that he has accomplished in his life and I found his career to be very inspiring.

When I first heard of what we were going to do for the oral history project, I had no idea the significance of what we were embarking on. I never quite understood how history was made or how people conducted informational interviews with a certain subject… I never thought that I would be making history in one of my classes, but I can honestly say it was a lot of fun, and I feel grateful for the lessons I’ve learned and the new outlook I have gained.

These kinds of experiential learning projects require a lot of coordination for the professor among students, between clients, and between students and clients. If/when I embark on this endeavor again, I will decrease the number of oral history subjects to four or five to make it more manageable in a 16-week semester.

I benefited from a grant that helped fund this project. But whether or not you have the time or funding for a large project, the bottom line is this: How are you incorporating active learning of your state’s community journalism into your journalism history class?

Teri Finneman is an associate professor of journalism at the University of Kansas and past chair of the AEJMC History Division. For more on this project, visit http://journalism.ku.edu/cherry-picked-ku-class-produces-oral-history-kansas-journalism.