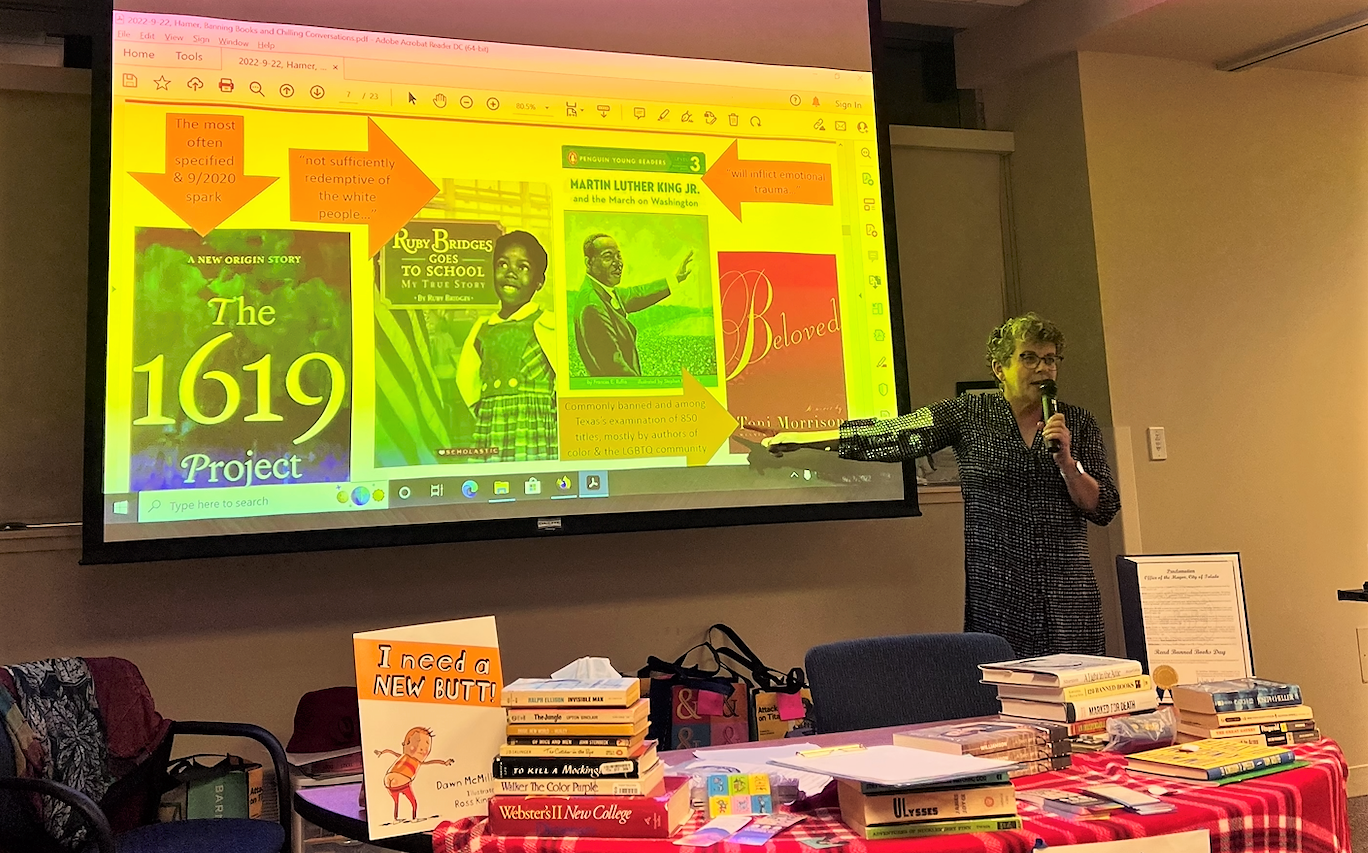

Lynn Hamer, professor in the UToledo Judith Herb College of Education, presents on Ohio HB 616 "Regarding Promoting and Teaching Divisive or Inherently Racist Concepts in Public Schools" at a 2022 UToledo Banned Books Week event.

By Paulette D. Kilmer, Professor and Coordinator of the UToledo Banned Books Week Vigil

For 25 years, we have joined the American Library Association in celebrating the right to read and think freely during Banned Books Week. We host an all-day program of 20-minute presentations to raise awareness of censorship. We give away door prizes, banned books, and light refreshments donated by sponsors. These gifts increase our web of involvement and make the Utoledo Banned Books Week Vigil a campus legacy event.

For 25 years, we have joined the American Library Association in celebrating the right to read and think freely during Banned Books Week. We host an all-day program of 20-minute presentations to raise awareness of censorship. We give away door prizes, banned books, and light refreshments donated by sponsors. These gifts increase our web of involvement and make the Utoledo Banned Books Week Vigil a campus legacy event.

Sometimes, people ask us why it matters if books are banned since the Internet empowers people to buy whatever they want. Chilling incidents in 2021 threaten the future of our right to read freely. For example, in Virginia, a judge ended two lawsuits to force Barnes and Noble to require permission slips from parents and to remove forbidden books from the state.

Censorship episodes occurred all over the country. For example, in the spring of 2022, Idaho, Texas, and Oklahoma considered laws to fine, fire, or imprison librarians who did their job and refused to remove books some in the community considered offensive.

When my former student, Aya Khalil, found out that her award-winning picture book, The Arabic Quilt, a story about a Muslim girl, was banned in Pennsylvania, she wrote The Book-Banning Bake Sale, which will be released in 2023. The resistance she faced is part of an unfortunate national trend of restricting books about diverse groups and by people of color.

In another episode, two parents living near Cincinnati asked Milford Exemption Schools to remove Julia Alvarez’s book about two girls resisting a dictator in the Dominican Republic during the 1960s.

The American Library Association listed 1,597 individual book challenges or removals in the organization’s 2021 Field Guide, explaining that many challenged or banned books go unreported, and so the number of targeted books in 2021 was much greater. PEN America reported that 2 million students in 86 districts throughout the United States lost access to books through these restrictions. The percentage of challenges at public libraries rose to 37 percent.

In April of this year, The Washington Post reported that the principal at an elementary school north of Columbus, Ohio, told an author to read another book to students other than the popular It’s OK to Be a Unicorn. The unicorns and rainbow lettering on Jason Tharp’s book convinced one parent it would recruit students to be gay. Actually, the protagonist, Cornelius, hides his true self from his horse neighbors fearing rejection; however, when they find out he is a unicorn, they accept him because it’s okay to be different. The story does not mention LGBTQ+ issues.

Although the second graders at a school in Byram, Mississippi, thought Assistant Principal Toby Price’s Zoom reading of Dawn McMillan’s I Need a New Butt was hilarious, the administrative top brass fired him for inappropriate and unprofessional conduct. Many former students, parents, and even strangers have donated to his GoFundMe account to help him pay court costs for suing to get his job back.

As ultra conservative groups form in Ohio and elsewhere, the attack on books, schools, and libraries gains momentum. For example, Ohio’s HB322 and 327 if passed will punish teaching controversial subjects, like racism, with denying students credit for courses, not funding schools, and suspending teachers’ licenses. Last year state legislatures drafted bills making teaching banned books a crime or outlawing lessons about race, the civil rights movement, or diversity if the content might make white people feel bad.

We cannot repair the damage done by white privilege or learn from our mistakes if we do not discuss them and then change our ways in the future.