Please introduce yourself and include your connections/role with AJHA.

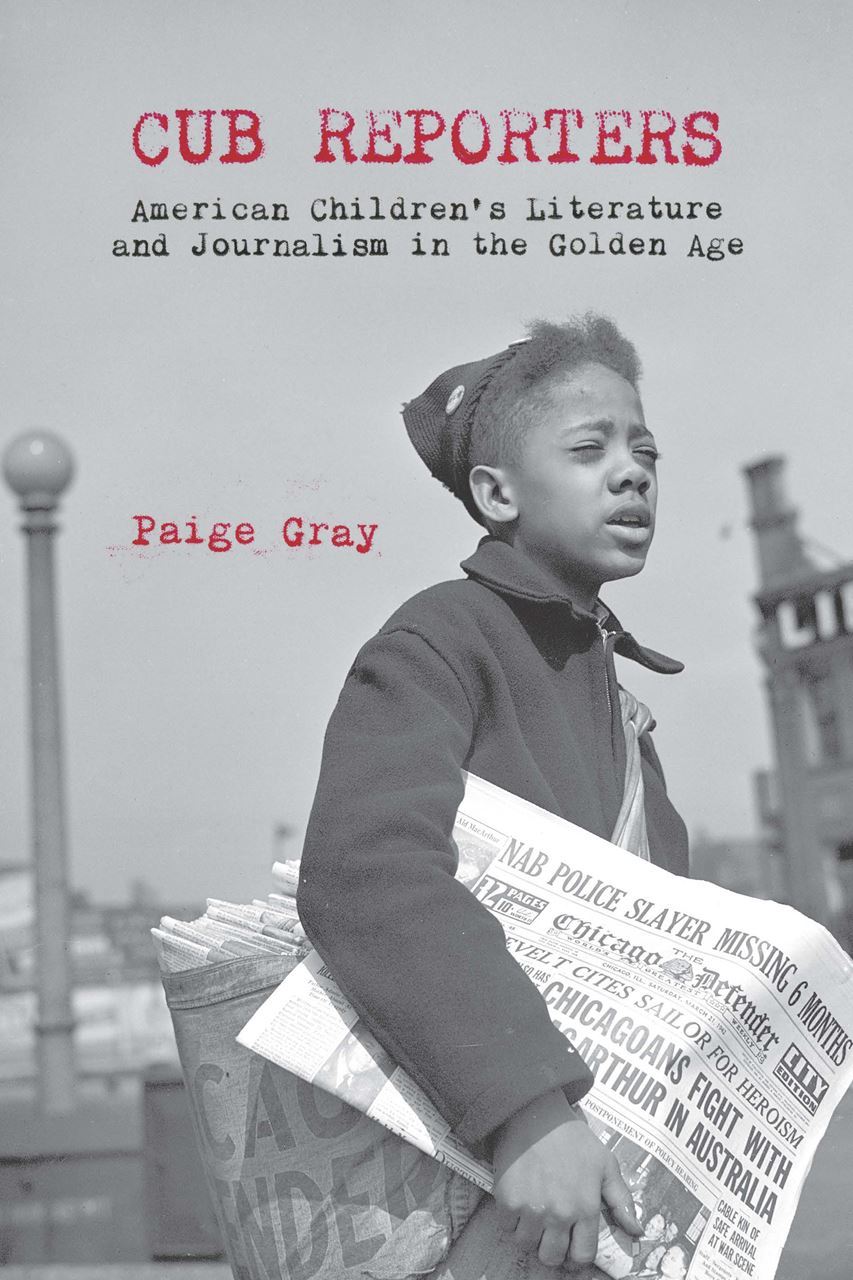

I'm Paige Gray. I'm a liberal arts professor at the Savannah College of Art and Design, and I've previously taught at Fort Lewis College, the United States Military Academy at West Point, and the University of Southern Mississippi. Much of the historical research that I did for Cub Reporters was rooted in journalism history, so I relied heavily on scholarship from the AJHA and its members.

What drew you to your topic/time period?

I've been fascinated by newspapers and journalism since I was very young. I used to recruit my friends in elementary school to be on my newspaper—but no one ever did their assigned stories! I ended up writing the stories and drawing the accompanying art all by hand on blank sheets of computer paper, designing it to look like a newspaper with columns and headlines.

My undergraduate honors thesis focused on The Wizard of Oz. Instead of going into a PhD program after my BA, I decided to go into journalism. After doing my MA in Chicago, I did newspaper work in Colorado and New Mexico, which I loved. But academia still nagged at me, and I was interested in further exploring children's literature.

When I started my PhD coursework and began thinking about my dissertation, I was trying to answer questions about my own interests—Why am I so fascinated by children's literature? Why am I so fascinated by journalism?

This led me to the Golden Age of children's literature—basically the latter part of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth—which is also a golden age for the American newspaper.

How did your thinking in the development of your topic start and then lead to this publication? Did it stray? Did you make any sudden and unexpected turns?

Cub Reporters was my dissertation. The project evolved over many years. In the early days, I focused on the overlap between the figure of the child and the figure of the reporter in American culture—how in the public imagination, these were agents of curiosity. They also seemed to have a reciprocal relationship, the reporter in the child, the child in the reporter. This led my initial outline and scholarship to be rooted in the concept of curiosity. As my work began solidifying into distinct chapters, new ideas and possibilities emerged. It wasn't until after I had solid chapter drafts that I made the connection to what I eventually termed "artifice."

Cub Reporters was my dissertation. The project evolved over many years. In the early days, I focused on the overlap between the figure of the child and the figure of the reporter in American culture—how in the public imagination, these were agents of curiosity. They also seemed to have a reciprocal relationship, the reporter in the child, the child in the reporter. This led my initial outline and scholarship to be rooted in the concept of curiosity. As my work began solidifying into distinct chapters, new ideas and possibilities emerged. It wasn't until after I had solid chapter drafts that I made the connection to what I eventually termed "artifice."

What surprised you most about this project?

So many things! The notion of "surprise"—the constant promise of discovery and newness—is why I love both reporting and scholarship. In particular, the ways in which American journalism and children's literature responded and reflected one another further revealed to me the constructed nature of childhood and adulthood as well as how we police ideas of curiosity and creativity.

In terms of the book's material and subjects, stumbling upon the Chicago Defender Junior was probably my biggest (and most delightful) research surprise.

What did you find to be your biggest challenge in working your way to completion of your monograph?

My monograph started as my dissertation, so when I began revision work, my professional world had changed—no longer was I graduate student with mentors surrounding me (at least in physical proximity), giving me guidance. Also, I was teaching full-time, so I had to be judicious with time. But more than that, I had to learn to really trust myself and the scholar I'd become. This was crucial since I recrafted the manuscript's organizing thesis.

What are you working on now?

I usually have several projects I'm juggling—articles and chapters in various stages of development. Ideas are never the problem. It's time! I recently finished work on a chapter for a collecting commemorating The Brownies' Book, published by W.E.B. DuBois and the NAACP in 1920. That research extends on my chapter in Cub Reporters on the Chicago Defender Junior by looking at other children's sections in Black weeklies around that period.

What topic would you like to tackle next?

I've been working on a new-book project since I moved to Atlanta and discovered the Center for Puppetry Arts. Puppetry may seem like a sharp turn from Cub Reporters, but it's really more of an extension. Cub Reporters considers how American children’s literature of the Golden Age subverts the idea of news; journalism, in the works that the book discusses, is not a reporting of fact, but a reporting of artifice. With this new project (tentatively called Play Things), I'm still thinking about artifice’s primacy to the human experience. While the cub reporters of children’s literature report the truth of artifice and relish it, the avatars of American puppetry similarly suggest the superseding condition of the human experience is that of creative invention—to be human is to create. The artifice of the puppet makes this notion inescapable. Through the creation of life via material means, puppetry promotes artifice, and promotes it through the acknowledgement of its process.