by Amy Lauters, Minnesota State University, Mankato

When I saw the coffin filled with copies of a working-class newspaper at the People’s History Museum in Manchester, England, the entire scope of the research project I’d gone to the United Kingdom to uncover changed.

The project started life as a proposed examination of how the Guardian had grown from its Manchester roots to become a national and international voice, and to what extent the Guardian played a role in building a community for its readers. The community-building function of media remains a keen interest of mine, and the McKerns grant I received from AJHA in 2018 provided me some of the funds I needed to take the trip to the U.K. to continue research in this area and lay the groundwork for future research.

However, when a friend suggested I visit the People’s History Museum on my first day in Manchester, those initial plans sharply diverged, as the newspaper in the coffin became my primary interest.

However, when a friend suggested I visit the People’s History Museum on my first day in Manchester, those initial plans sharply diverged, as the newspaper in the coffin became my primary interest.

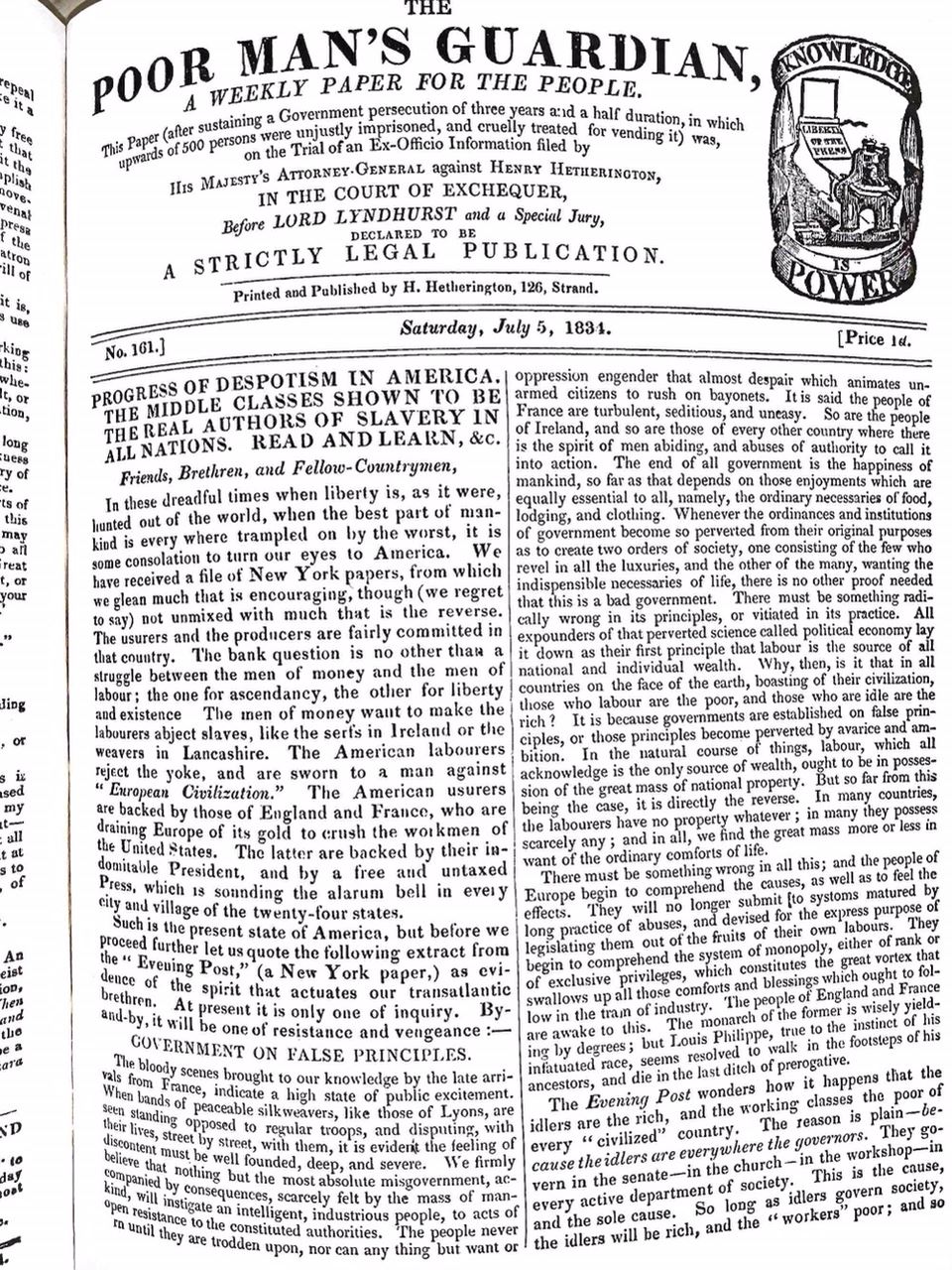

According to the plaque next to the coffin, the newspaper, called the Poor Man’s Guardian, had been illegal and regularly smuggled about the country in coffins of this kind in an attempt to keep the bearer from being jailed and fined for possessing it.

Several bits of that short story immediately piqued my interest: First, the word “illegal” applied to “newspaper” nearly guaranteed that I’d take note. Second, the lengths to which the publishers and readers of the paper apparently went to connect suggested to me a level of commitment that needed further exploration. And third, I immediately wondered if the Poor Man’s Guardian had any relationship at all to the current national Guardian.

The third question was easily answered with a trip to the museum’s front desk, where a helpful attendant directed me to the museum’s basement and its gorgeous newspaper archive. The archivist showed me the bound copies of the Poor Man’s Guardian, which was entirely separate from the original Manchester Guardian. The museum also houses an excellent selection of books about the press and labor history in Britain, which proved to be valuable in contextualizing the rest of the story I was beginning to untangle.

The timing of my visit was fortuitous; many organizations in the city of Manchester had begun rolling out events to commemorate the Peterloo Massacre, a protest for universal suffrage that ended in bloodshed in 1819. The Manchester paper was founded shortly after it, and I already had established that the Manchester paper had evolved into the national Guardian. (While an office remains in Manchester, its primary offices were moved to London in the mid-20th century. I visited both while I was in the U.K.) The rise of the Unstamped newspapers has its roots in Peterloo, as one government response to that event was to re-impose the newspaper stamp, making it economically challenging to produce and to purchase newspapers as well as requiring content to be pre-approved.

The timing of my visit was fortuitous; many organizations in the city of Manchester had begun rolling out events to commemorate the Peterloo Massacre, a protest for universal suffrage that ended in bloodshed in 1819. The Manchester paper was founded shortly after it, and I already had established that the Manchester paper had evolved into the national Guardian. (While an office remains in Manchester, its primary offices were moved to London in the mid-20th century. I visited both while I was in the U.K.) The rise of the Unstamped newspapers has its roots in Peterloo, as one government response to that event was to re-impose the newspaper stamp, making it economically challenging to produce and to purchase newspapers as well as requiring content to be pre-approved.

While none of the newspapers in the museum’s collection were digitized, I was given permission to go through them in the archive’s reading room and to digitize the copies I wanted to take myself, for a small fee per day. I quickly found myself sucked into the 19th century, reading week after week of the Poor Man’s Guardian and learning about a working-class community that was agitating for political change. The community had an underground network of distributors of the paper, which was Unstamped and therefore illegal.

The publisher of PMG, Henry Hetherington, got arrested and imprisoned three times during the paper’s run for the crime of publishing the paper. His editor, James Bronterre O’Brien, published in Hetherington’s stead, raising funds to replace presses that had been seized, coaxing readers to send in the minutes from their union meetings, publishing letters from readers incensed over numerous issues, including Hetherington’s imprisonment, and publishing a list, at the back, of all who had subscribed or contributed to the bail fund that had been set up. O’Brien also published notices looking for men without ties to distribute the paper, promising that if they were caught, their fines would be paid from the fund.

Hetherington and O’Brien rarely used bylines in the paper itself, and it would have been foolish to do so given the illegality of the work. Neither did they specify many of the techniques they used to distribute the paper, and again, it would have been foolish to do so. Some of the tales told now no doubt have roots in oral history that will never be verified.

Hetherington and O’Brien rarely used bylines in the paper itself, and it would have been foolish to do so given the illegality of the work. Neither did they specify many of the techniques they used to distribute the paper, and again, it would have been foolish to do so. Some of the tales told now no doubt have roots in oral history that will never be verified.

The Poor Man’s Guardian also provides an example of a newspaper that folded once its purpose had been fulfilled. It had been founded to agitate for an appeal to the Stamp Act, as well as to provide a forum for working-class activists who were seeking universal suffrage, unionization, and representation. According to the editors, once the Stamp Act had been repealed, it was no longer as popular, and it no longer made enough money to sustain itself. PMG folded in 1836, and Hetherington and O’Brien moved on to other projects and publications. The publication itself is cited by British Labour scholars as a cornerstone of Labour Party movement.

My experiences traveling with the McKerns Grant provided an object lesson in the value of actually visiting archives and historic sites, rather than relying exclusively on digital archives. The work I’d intended to do became derailed by a story seldom told in the United States. And yet, that story opened up several new directions for research and questions about the nature of a free press and its development in the United States as opposed to Great Britain that could prove fruitful for future study. Certainly, the image of the newspapers in the coffin will never leave me.

Visit the People’s History Museum online if you can’t make it to Manchester in person: https://phm.org.uk

All images courtesy of Amy Lauters. From the top: interior of the People's History Museum; front page of The Poor Man's Guardian; a printing press at the museum.

Lauters also did video diary posts to send home to her family during her trip. The below clip is a from a visit to John Rylands Library: