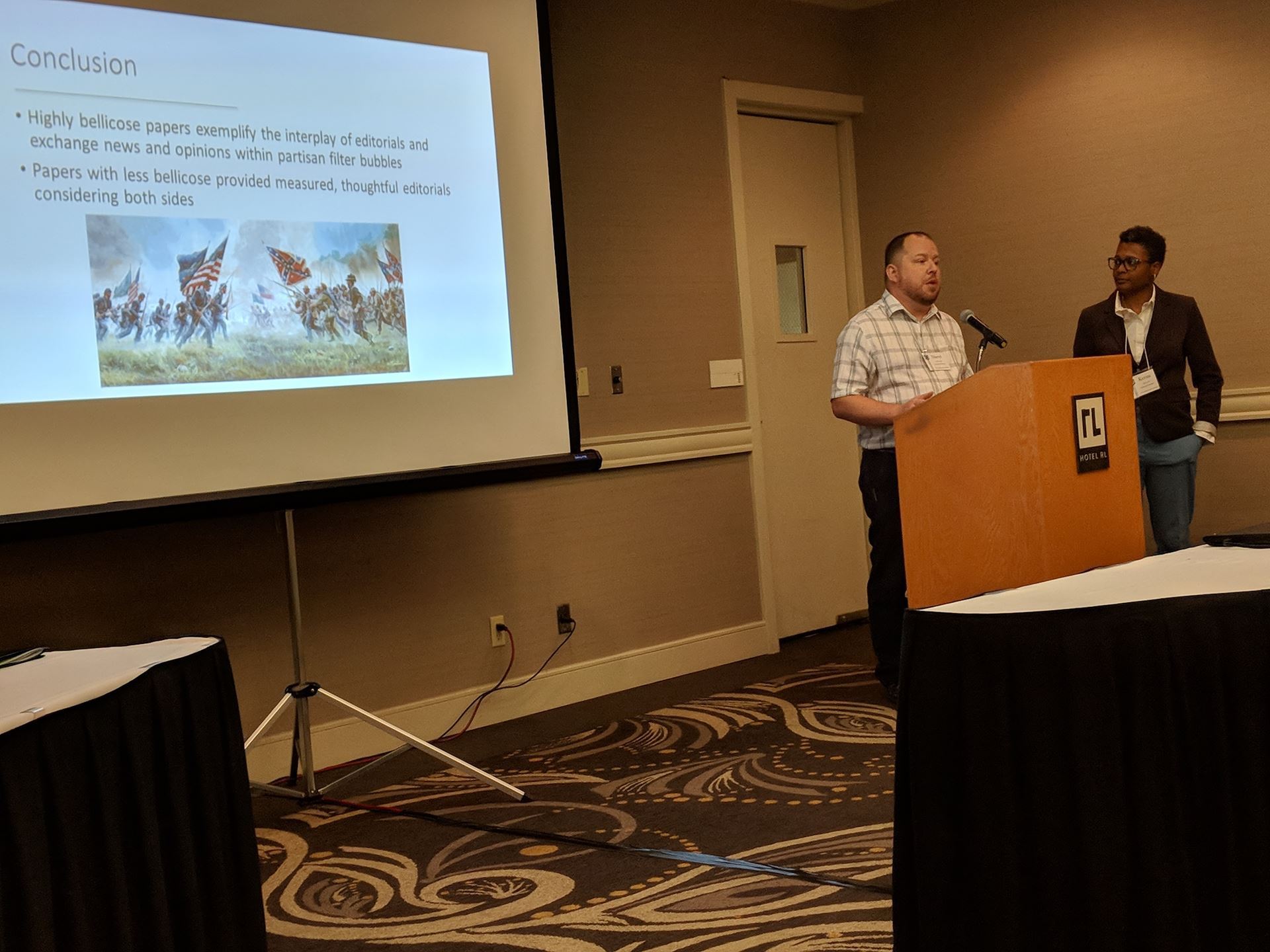

Wayne State doctoral candidates Darryl Frazier, left, and Keena Neal present the Research Gang’s paper “Spinning toward Secession: The Interplay of Editorial Bellicosity and Exchange News in the Press before the American Civil War,” at the 2018 AJHA annual conference in Salt Lake City, Utah. The manuscript is now in press in the Southeastern Review of Journalism History.

Wayne State doctoral candidates Darryl Frazier, left, and Keena Neal present the Research Gang’s paper “Spinning toward Secession: The Interplay of Editorial Bellicosity and Exchange News in the Press before the American Civil War,” at the 2018 AJHA annual conference in Salt Lake City, Utah. The manuscript is now in press in the Southeastern Review of Journalism History.

Michael Fuhlhage is an associate professor in the Department of Communication at Wayne State University.

When and how did you become involved in AJHA?

I took Earnest Perry’s grad seminar in media history during my master’s program at the University of Missouri-Columbia. He encouraged me to submit my paper, and it got accepted for the AJHA 2005 conference in San Antonio. I’ve been to all but one AJHA conference since then, and my involvement deepened with panel, paper, and research in progress submissions during my PhD studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Frank Fee, my advisor, and Barbara Friedman, who was on my dissertation committee, really encouraged me to get involved. Since then, I’ve been a frequent paper and panels presenter, panels coordinator, research committee chair, and a member of the AJHA Board of Directors.

Your paper on the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act in Detroit River Borderlands Newspapers recently won AJHA's awards for outstanding paper on a minority history topic. What led you to that particular subject?

Part of it came from being an opportunistic archive pack rat, and part of it was interest in the events that led up to the American Civil War. Some of the journalists I researched for my first book, Yankee Reporters and Southern Secrets, were involved in abolitionism and the Underground Railroad. That led more famously through Philadelphia and New York, but it’s a real point of pride for Detroiters that the UGRR’s western network running through Detroit was nearly as busy. I noticed that Michigan journalists’ part in that story had been neglected, with the exceptions of recent works by Afua Cooper and others, and I’ve become more and more interested in local and regional history here in Michigan.

You've been successful forming a research gang with several students. Talk a bit about your process when you're working with a team of students?

It started when I was a panelist for a grad student brown bag session in my department on research agendas and how to get them off the ground. A couple of colleagues in the Wayne State Department of Communication and I did a sort of show and tell about what we were working on and how we got interested in it. And I was brimming with excitement and ideas about news and editorials about the secession movement in 1860-61 after doing research at the American Antiquarian Society in summer 2015. I mentioned I’d like to collaborate with grad students on the primary sources I had brought back. That led to a couple of students following me up to my office to look at a database I’d started that tracks the flow of secession news and opinion from one newspaper and region to another, and they followed me down the rabbit hole. That turned into an AEJMC History Division paper and then an article in American Journalism. That’s how the Research Gang started.

Here’s how the Fugitive Slave Act paper came together: The first thing to remember is most of this in the pandemic lockdown. Campus was closed. Vaccines weren’t even available yet. It would have been easy to give up and sit it out until we could get together in person. But I knew that we had already gathered the primary sources that we needed to explore Detroit journalism’s role in that story. One of the first things I had done after arriving at Wayne State University in 2014 was to spend a few hours combing the card catalog at the Detroit Public Library’s Burton Historical Collection and learning about their Michigan newspaper holdings. A couple of titles stuck out to me: complete runs of the 1851-52 editions of Henry Bibb’s Voice of the Fugitive and the anti-slavery Baptists’ Michigan Christian Herald in nearly perfect condition in bound volumes. I knew the Detroit Free Press was a pro-slavery voice among the city’s newspapers and thought it would be interesting to compare how the three framed the slavery issue in the same time period. It can be hard to find full runs of a single newspaper, so we were really fortunate to find three in the same time period for direct comparison of their framing of slavery. So in the fall of 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, Wayne State doctoral candidate Darryl Frazier and M.A. student Eloise Germic and I set out to make digital images of each page of the Voice of the Fugitive and Michigan Christian Herald, and we put them in a shared Google Drive file. Digitizing those papers was initially an exercise in archival methods. We didn’t know exactly what might be done with them at the time. Eloise graduated and moved on to doctoral study elsewhere, and other matters like my going up for tenure, Keena preparing for comps, and oh that’s right, the pandemic hit. Darryl and I pretty much forgot about the digitized newspapers until we all got past those other events and figured out how to teach remotely.

My model for collaboration with graduate students was my professor at UNC, Donald L. Shaw, who would lead free-flowing discussions first about possible general topics, research questions we might ask, how we might locate primary sources to answer those questions, and how to organize our findings. He put a lot of care into creating an agenda for each research team meeting, explaining steps in the research process, working with us to set deadlines, and analyzing the evidence. So I followed that model. The core of the Media History Research Gang at Wayne State consists of myself and students who took my graduate seminar in agenda setting, my doctoral advisees, and M.A. and undergrad honors students in my American journalism and media history course.

I got the ball rolling by convening an organizational meeting to decide which of a list of ongoing research projects they’re most interested in. The Research Gang had tackled the flow of news about secession in 1860, newspaper news and opinion during the secession crisis, and the work of a Wayne State journalism alumnus who had covered the Civil Rights Movement in the South in the 1960s. Variations on those topics were on the list, but we also had these really rich primary sources that we hadn’t done anything with yet that concerned the struggle over slavery in the Detroit River borderlands connecting Michigan and Ontario. I think we were all really curious about what we would find once we started to explore them, so that became the topic. Then it became a matter of dividing the work according to our interests and skills. We used Zoom, email, and Google Drive to coordinate on the project.

Keena, who is my doctoral advisee, Darryl, and I had already collaborated on a couple of projects, and as new members of the Research Gang each of them had started with compiling, analyzing primary evidence, and discussing how their findings fit with everyone else’s. Darryl had photographed the Voice of the Fugitive, so he already had a stake in that title. Keena was intrigued in the idea of interracial cooperation and allyship in the fight against slavery. The Michigan Christian Herald fit that theme, so that became her object of analysis. Anna Lindner, another of my doctoral advisees and the junior partner on the team for this paper, took on analyzing the Detroit Free Press, which we accessed through a database. She also wrote our methods section in consultation with me based on team discussions of how we would execute the study.

As the established historian, I had the most solid grounding in the literature, so I wrote the background section. Keena, Darryl, and Anna started reading and taking notes on their newspapers while I completed the background section—and that really was crucial for everyone to understand enough about the political, economic, and cultural context in order to do their analysis of their respective newspapers. We touched base about whether the research questions guiding us were really doing the job and adjusted after everyone had swum in the evidence a bit. Once everyone was finished with analysis, we reconvened as a group to make sense of what had been discovered and to assign writing and editing duties. Keena took on writing the introduction and Anna wrote the conclusion. My role at this stage was to merge all the parts together, line edit it so it read as one piece, and make sure we hit deadline. We all proofread. For the conference presentation, I feel that it’s my students who need the most exposure as people bound for the job market soon, so as long as they don’t have something heavy at conference time like defending comps or a dissertation prospectus I offer that role to the students. My role then is to prepare rough slides that they’re free to tweak and otherwise be their cheerleader.

What do you believe is the value of co-authoring with students?

There are so many valuable things that come out of it. Of course, my students learn how to execute a historical research project step by step. But I always learn something new from them because they have the benefit of having recently studied with my faculty colleagues from disciplines different from my own. Because of this, the students often bring different ways of seeing to a project. Here’s a confession: I recognize that I’ve sometimes been guilty of methodological sloppiness. Working with my students keeps me on my toes in terms of rigor in our methods of analysis. I benefit from their knowledge and expertise as they benefit from mine. In addition, it’s really satisfying to see how the students are growing as each phase of a project comes together. And it fills me with pride when I see them present the work that we completed together.

How do you incorporate research into your teaching?

For one thing, teaching historical methods from scratch to the Research Gang students has made me pay close attention to how to explain the steps that I outlined above in a step-by-step fashion. This semester, I’m experimenting with a hybrid group/individual final project for my undergraduate journalism history students. I created a list of 13 topics through various periods in U.S. and Detroit history. Then I surveyed my students and assigned them to nine teams. This way, they have a degree of ownership in the project in that they were able to pick something they were already relatively fascinated with. I’m getting them off the ground by guiding them as they formulate initial research questions, master some of the secondary literature for their topic and period, refine keywords to use in a newspaper database, and analyze and organize their findings. This pretty much follows the Research Gang model, but it feels a little like building an airplane while it’s taking off. It’s a fun challenge, and I’m learning a lot in the process by examining secondary lit about topics and historical periods that haven’t necessarily been at the center of my own bull’s-eye of research interests.

What are you working on next?

I’ve got a few projects at various stages of completion. I’ll just describe one of them here: It’s an extension, reorganization, and rewrite of my dissertation on the prehistory of stereotypes about Mexicans in the American nineteenth-century press.

What are some of your hobbies or interests outside of academia?

Gardening is one. During the pandemic lockdown I needed to do something that made me feel like I was in control of something since so much was beyond our control. So I took an online extension course in vegetable and fruit gardening. I’ve dabbled in music for years and have a piano and a couple of electric and a couple of acoustic guitars. I love the arts of all kinds and visit art museums when I need to refill my cup of joy and inspiration. But my newest toy is a Fender Mustang P/J short-scale electric bass guitar. For ages, I have loved the play of Talking Heads’ Tina Weymouth and the Rolling Stones’ Bill Wyman, who both played Mustangs. My big bass heroes are Geddy Lee and John Entwistle, but Rickenbacker and Alembic are a little rich for my taste, at least for a beginner’s bass.